Montreux Collaborative Blog

Digital Public Financial Management Systems in Ghana’s Health Sector: Lessons from the Frontline

Mark Akanko Achaw, Collins Boateng Agyenim, and Paul Abonyo

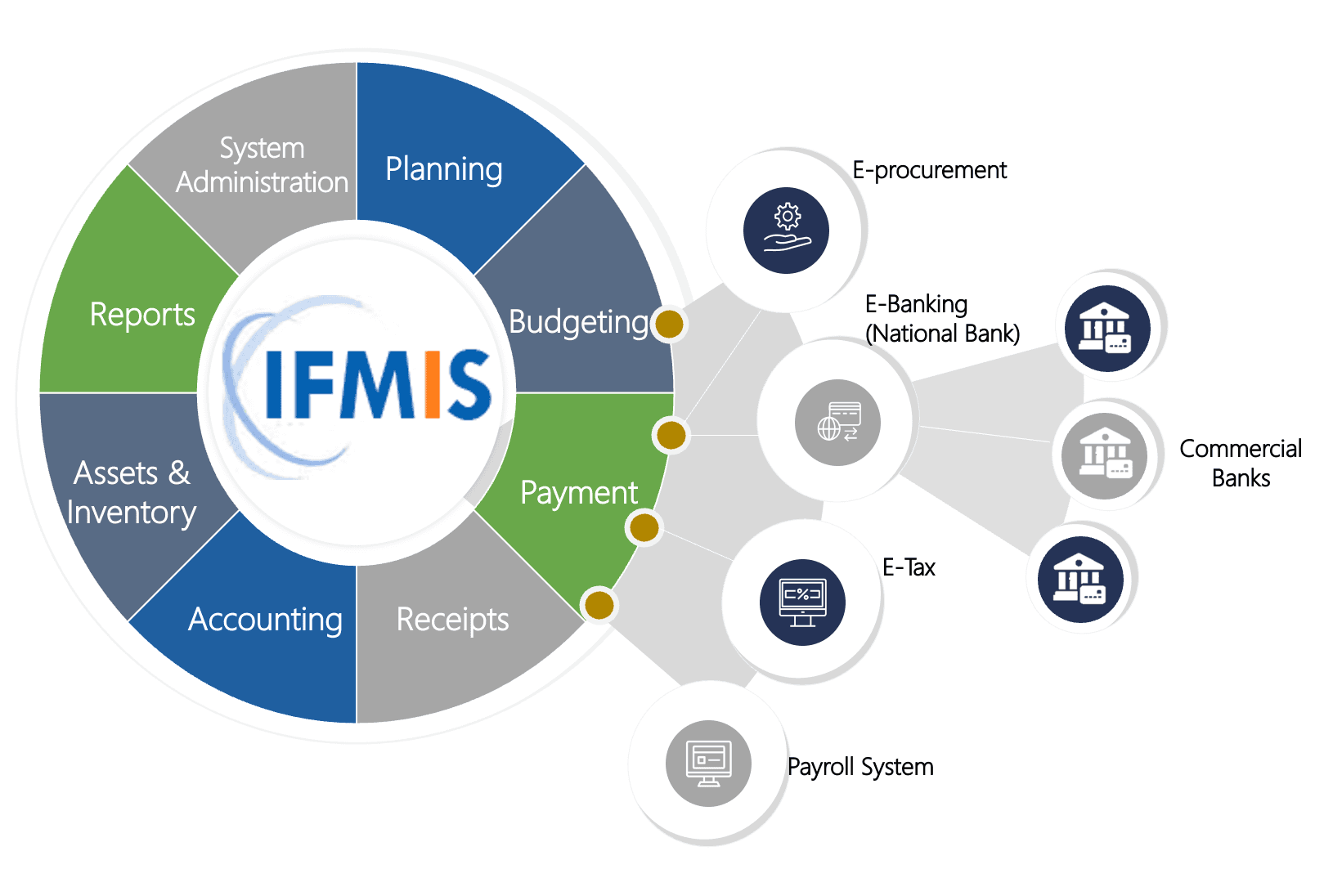

In the health sector, every second counts. Diagnosing a condition, treating a patient, or getting essential medicines to a clinic—very moment wasted not only causes inefficiencies, but can also mean lives lost. When Ghana launched ambitious public financial management (PFM) reforms in the 2010s, the health sector was both eager and cautious. The reforms including the 2015 PFM Reform Strategy, the Public Financial Management Act (2016), the revised Procurement Act, and the rollout of the Ghana Integrated Financial Management Information System (GIFMIS) promised a new era of greater efficiency, transparency, and accountability. But health sector managers worried that these changes might also introduce rigid procedures and bottlenecks that could slow financial flows and, in turn, delay life-saving services. As a result, while GIFMIS was adopted across most sectors, the Ghana Health Service (GHS) continued to rely on its own internal systems for planning, reporting, and expenditure tracking.

More than a decade later, it is useful to look back at the push to introduce new public financial management systems and to consider the challenges that arise when applying them to a complex, high-stakes sector like health.

Why GIFMIS Wasn’t Enough for the Health Sector

GIFMIS was designed and customized as a government-wide financial management platform, built to ensure consistency and control through a standardized chart of accounts. This harmonization was vital for national oversight. However, its centralized architecture also means that even minor system adjustments must be routed through the Ministry of Health (MOH), triggering lengthy bureaucratic procedures, including formal clearances and multi-level approvals.

For the health sector, where programmes often emerge rapidly in response to outbreaks, emergencies, or shifting disease patterns, this rigidity posed a serious concern. Health managers worried that GIFMIS would not be responsive enough to support the sector’s fast-evolving operational needs. This early tension between compliance and operational responsiveness shaped much of the health sector’s digital transformation journey. As a result, many GHS departments and frontline facilities relied for years on alternative digital tools that better served their needs until recently when the leadership set the path toward fully transitioning to the national PFM systems.

Homegrown Solutions

Over time, GHS adapted and developed a patchwork of internal digital financial management tools to fill the gaps:

- e-Transaction System: An Excel-based tool shared through Dropbox. It became the main financial transaction tool for district health directorates and facilities because it is accessible, flexible, and easy to use. It allows frontline units record and combine financial data before later extracting and uploading it into GIFMIS.

- Sage 300 ERP (Accpac version 6): Used at the national and regional levels. It provides stable, core accounting functions but is expensive to maintain and does not offer the level of detail needed by facilities. It is supported by the PERESOFT cashbook module.

- Ghana Logistics Information Management System (GhiLMIS): A logistics tool that tracks stock levels and the movement of commodities, and also helps with forecasting and quantification. However, without integration to budgeting and expenditure systems, the logistics data remains disconnected from financial planning, limiting the sector’s ability to link commodity consumption trends with budget performance.

- Planning and Budgeting Management Information System (PBMIS, 2019): A health-specific planning and budgeting tool that links financial planning with disease burden, coverage needs, and sector priorities. Unlike GIFMIS, it integrates epidemiological and service delivery data directly into the budgeting process, helping align resources with health outcomes. PBMIS is one of the most significant innovations in health-sector PFM, yet it still lacks automated integration with GIFMIS. This gap means that budget formulation and budget execution continue to operate in separate digital environments.

For GHS, PBMIS in particular has been a game-changer. It allows the health planners to answer not just “how much money is being spent” but “what health problems are being solved.”

The Push for Full GIFMIS Adoption in Health

Despite the strengths of these internal systems, GHS faced pressure to comply with national requirements. Audit concerns, budget mismatches, and provisions in the 2016 PFM Act made it clear that wider use of GIFMIS was non-negotiable.

With support from partners, including the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), GHS began a major push to roll out GIFMIS across all its Budget Management Centers (BMCs). This initiative, supported by the FCDO Strengthening Ghana Health Service’s Public Financial Management Capacity Project (SPFM), is training more than 2,000 users, deploying both the Financials (P2P) and Hyperion budgeting modules to GHS entities including health facilities at the subdistrict level.

Importantly, during customization of the GIFMIS for the health sector, GHS secured a critical “win”: it successfully advocated for the activation of the “project segment” in the chart of accounts. For the first time, this will allow project-specific expenditure tracking, a big step forward for transparency and donor confidence. At the same time, GHS has recognized the limitations of GIFMIS and continues to use PBMIS in parallel. The result is a hybrid approach: compliance with government-wide standards while preserving sector-specific flexibility.

Lessons Learned

The Ghana Health Service’s experience shows that digital PFM systems are not just about installing software. They are about balancing control, compliance, and flexibility in a way that serves both government and sector priorities. Three key lessons stand out:

- One size doesn’t fit all. A government-wide system ensures consistency, but sectors like health need complementary tools to capture their complexity. Rigid uniformity can be counterproductive.

- Flexibility drives ownership. Systems must adapt to evolving realities, whether that is a new disease outbreak or shifting donor priorities. Periodic reviews, decentralized customization, and user-friendly systems and tools are essential.

- Integration is better than substitution. Instead of forcing sectors to abandon their tools, governments should look for ways to integrate them with national systems. This allows for both compliance and relevance.

- Change management determines system adoption. Digital PFM reform succeeds when frontline staff understand the purpose of the system, see improvements in their day-to-day work, and receive responsive technical support.

- Strong governance safeguards sustainability. Effective digital PFM reform depends on clear system governance: well-defined user rights, structured data management protocols, reliable troubleshooting mechanisms, strong cybersecurity standards, and coordinated inter-agency collaboration to keep the system secure, functional, and sustainable.

Looking Ahead

Ghana’s health sector is now closer than ever to full alignment with GIFMIS, but crucially, this progress has not come at the expense of responsiveness. By pursuing a hybrid approach to integration, the GHS is demonstrating that digital PFM reform delivers the greatest value when national systems and sector-specific innovations reinforce each other rather than compete for space.

This is why Smart PFM systems (enabled by AI) are so essential—providing flexible systems that align fully with national PFM rules while adapting to sector-specific dynamics and needs. Equally important is building an end-to-end data pathway that links planning, budgeting, execution, monitoring, and health outcomes, closing the loop between expenditure and performance.

For countries pursuing similar reforms, the lesson is clear: don’t chase uniformity for its own sake. Build adaptable systems that keep national oversight strong but also empower sectors to link financial resources to performance outcomes matter most.

After all, in health, as GHS reminded us from the beginning, every second and every dollar counts.

Authors affiliations: Mark Akanko Achaw (Palladium), Collins Boateng Agyenim (Ghana Health Service), and Paul Abonyo (Palladium)

The authors can be reached by email at mark.achaw@thepalladiumgroup.com

December 2, 2025